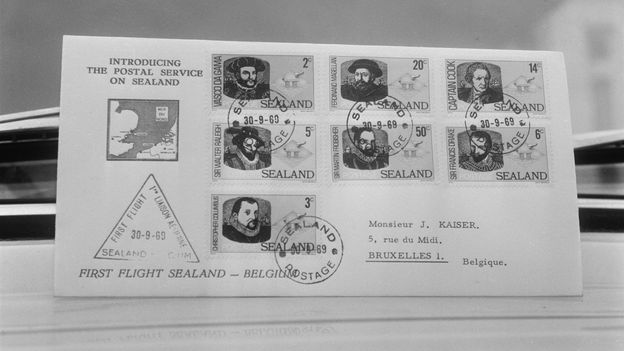

This is the country Sealand. It has its own government, stamps, passports & even a soccer team. There are 27 official residents.

This story starts with an email that I will never forget.

On a late spring morning in mid-May, Prince Michael of Sealand, leader of a micronation called the Principality of Sealand, messaged me with five clear-cut words: “You can speak to me”.

It was a peculiarly short prologue to a barely believable story that would take me on a historical journey through the realms of self-proclaimed kings, territorial claims, historical anomalies and World War Britain. And, as unlikely as it sounds, pirate radio stations and cockle fishing, too.

Another fact about this exchange: it thrilled me. I’d never received an email from a prince before, and it was unlikely to ever happen again.

Of course, I’d come across the story of Sealand, a tiny principality off the English coast of Suffolk that claims to be the world’s smallest country, before. The micronation, in fact a solitary World War Two-era anti-aircraft platform, was first erected in 1942 as HM Fort Roughs, an armed sea fort outside of Britain's then territorial limit in the North Sea. From being occupied by up to 300 Royal Navy personnel at the height of the war to its final evacuation in 1956, the gun station was soon abandoned and left to fall into disrepair. That is, until 1966, when a former British Army major occupied it, giving birth to a new, tiny micronation.

I certainly didn’t think it’d be a story that’d carry on for 50-odd years

Today, it remains 12km offshore, visible up close only by boat. To look at, it is nothing special: a blasted-looking platform with a smattering of container-like buildings on top. To disembark requires braving whipping winds and moshing waves while being winched up by a crane.

But there was plenty more I didn’t know. Stories about dawn helicopter raids for one. Others about devious gangsters and an attempted coup by shady European businessmen. Even a revelation from a declassified UK government document describing the frontier as a “Cuba off the east coast of England”.

It all sounded like the plot to a B-movie, born from the pen of a Hollywood scriptwriter. Not from the determination of a working-class family from Essex who turned this outpost into a micronation. And yet here, in this lonely North Sea spot, dreams were born, freedom from authority was granted and British eccentricity — in all its pomp and pageant — ruled.

You may also be interested in:

• The tiny 'country' between England and Scotland

• Europe's strange border anomaly

• The 'nation' with a useless passportFour days later, Prince Michael of Sealand answered my call. The micronation leader was armed with riveting tales, many of which appear in his memoir, Holding The Fort. And he was ready to divulge Sealand’s story, which largely remains unknown by the rest of the world.

“I was only 14 when I first came out during my school summer holidays to help my dad, and I thought it’d only be a six-week adventure,” he said, speaking from his main home, a bungalow on the Essex coast. “I certainly didn’t think it’d be a story that’d carry on for 50-odd years. It was a strange upbringing, as sometimes we stayed for months on end, waiting for the boat to bring supplies from the mainland. I’d look out at the horizon and all I could see from morning to night was the North Sea.”

Such nostalgia of a place shouldn’t dilute the complexities of Sealand’s contested geopolitical circumstances. No country formally recognises Sealand, even if Prince Michael says the micronation has never asked for recognition.

“We don’t expect any either,” he added, bluntly. “Remember, the platform was built illegally outside British territorial waters during a time of war – but everyone was too busy to care. The British should have destroyed it when they had the chance, but they never got ‘round to it. Now, decades later, Sealand is still here.”

By virtue of their size – just 0.004 sq km in Sealand’s case – micronations require us to reset our sense of scale. But what draws people to creating their own in the first place? For George Dunford, co-author of Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations, it’s a dissatisfaction with their current government and “wanting to do things their own way”.

“Sealand is a special case because it has got away with it for so long and ducked laws,” said Dunford. “In the United States, the family would have been seen as dissidents, but the UK was a more tolerant place back in the 1960s – and bureaucrats probably thought it more trouble than it was worth to tackle the problem. They had a few tries and there were takeover attempts, but it survived. It’s a real survivor of the micronations community.”

As a rule, most micronations trace their de facto recognition back to 1933 when the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States was signed by international leaders, including then US President Franklin D Roosevelt. In it, the legislation sets out four main criteria for statehood.

“The Montevideo Convention is mostly commonly used to define a micronation, which calls for a population, territory, government and relations with other states,” Dunford explained. “It’s the last one that makes micronations most agitational because they often try to provoke other states into recognising them. Sealand eschews it by saying it’s a sovereign state with its own ruler.”

The British should have destroyed it when they had the chance, but they never got round to it

Every nation has a convoluted origin story and Sealand’s is more Kafkaesque than most. It begins in 1965 when Prince Michael’s father, Paddy Roy Bates, a former British Army major turned fisherman, began Radio Essex. This pirate radio station was located offshore on Knock John, another disused naval fort near HM Fort Roughs. Such was the popularity of the illegal offshore stations at the time, the UK government then rolled out the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act of 1967. It had one purpose: to shut them all down.

Seeing an opportunity, Bates moved his operation onto HM Fort Roughs — further out to sea and, and more importantly, further into contested international waters. Like Knock John, it was tenantless and in a state of disrepair – and, whether legal or not, Bates assumed control of the outpost on Christmas Eve 1966. Nine months later, on 2 September 1967, he declared it the Principality of Sealand – a romantic gesture on his wife Joan’s birthday. Shortly after, the entire family moved in.

At its peak, in the early 1970s, Sealand had 50 people living on the platform, including extended family and friends and maintenance personnel. At the same time, it became an unlikely symbol of anti-authority protests in the UK; but behind the scenes, the bohemian operation was run on a far more basic level.

“Nothing worked,” Prince Michael told me. “We started with candles then upgraded to hurricane lamps and pump-up generators. The good thing was it is as dry as a boat; if you didn’t know you were out at sea you could never tell. I spent years and years out there – but, you know, it was home.”

Ever since, the rogue state has embraced nationhood. It introduced its own coat of arms and constitution. There’s a flag, football team and anthem, while the currency bears the portrait of “Princess Joan” and around 500 passports have been issued. The motto of the micronation, over which Prince Michael and his three children (James, Liam and Charlotte) and second wife (Mei Shi, a former major in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army) continue the Sealand dynasty, reflects a love of unshackled independence. “E Mare, Libertas” it reads. Or, “From the sea, freedom”.

“My father never set out to start his own country,” explained Prince Michael, who is also owner of a cockle fishing business that exports seafood to Spain. “He was principally offended by the UK government wanting to close his pirate radio station. And ever since, we’ve fought the British government all the way – and won. Sealand still maintains its independence.”

By any measure, the most controversial episode in Sealand’s history took place in 1978. Buoyed by thoughts of an international takeover, a group of German and Dutch mercenaries stormed Sealand one August night, only to be captured at gunpoint by the Bates family and held hostage.

“It led to the German ambassador and an official delegation coming from the embassy in London by helicopter to hold negotiations for his release,” Prince Michael said nonchalantly, playing down the drama of the incident. “So, by negotiating, they in fact gave us de facto recognition.”

In the United States, the family would have been seen as dissidents

What’s not up for debate is that independence doesn’t come cheap. To fund Sealand’s operational costs – including two full-time security personnel who live on the micronation year-round – Sealand’s online store sells T-shirts, stamps and royal titles. A Lord, Lady, Baron or Baroness peerage costs £29.99.

The usual customs and immigration norms don’t apply either, of course. It’s only possible to visit with an official invitation from the prince, who visits two to three times a year, and beyond the shoestring staff, no-one currently lives here.

“Sealand has always teetered on being precarious, but the current prince runs the place on more of an even keel these days,” said Dunford. “That’s what I love about micronations. The way they parody the pomp of real nationalism is fabulous.” As a case in point, Sealand receives in excess of 100 emails a day, with requests from wannabe citizens from Delhi to Tokyo keen to pledge allegiance to the flag.

“Our story still fires people up,” Prince Michael concluded. “We don’t live in a society where people like being told what to do, and everybody loves the idea of liberty and freedom from government. The world needs inspiring territories like us – and there aren’t many places like this that exist.”

In Bates’ life, one thing has remained reassuringly constant: Sealand still stands tall, watching silently over the North Sea. For the rest of us, it is a curious place so near to the UK and yet so far – an elsewhere of this world so extraordinary and different that it almost feels impossible.

Places That Don’t Belong is a BBC Travel series that delves into the playful side of geography, taking you through the history and identity of geo-political anomalies and places along the way.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Comments

Post a Comment