In the 1960s, Bell Labs created a picture phone where people could look at each other while talking on the phone.

It was 50 years ago, on April 20, 1964, and during the subsequent months of the World's Fair at Flushing Meadow Park across from the brand-spanking-new Shea Stadium in Queens, New York, that Mr. and Mrs. America got their first chance to make a video telephone call on Bell's Mod I (Model I) Picturephone. Fair-goers had to wait on line at the Bell Telephone exhibit at the northeast tip of the Fair to hold a 10-minute visual talk with a complete stranger at a similar Picturephone exhibit at Disneyland in California.

Can you see me now?

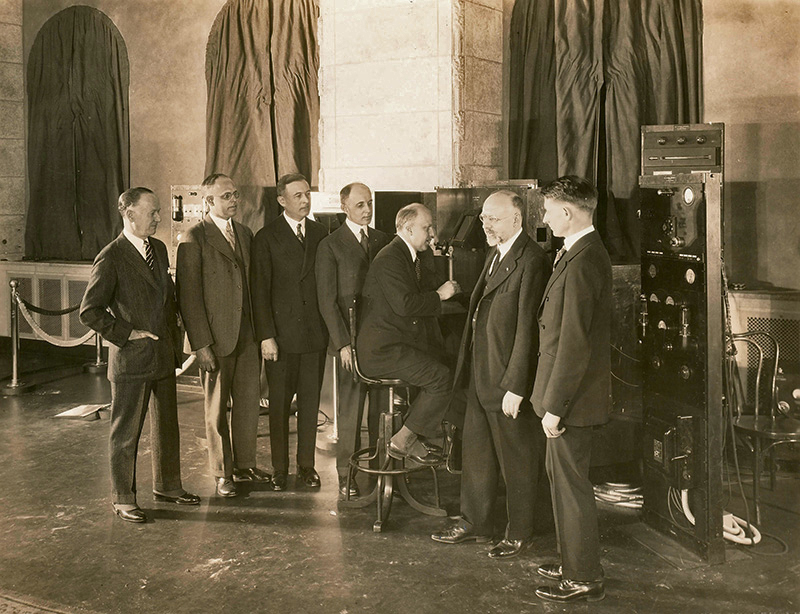

Bell Telephone Laboratories, the research arm of the emerging communications giant, began work on creating an actual "picture-phone" device in the 1920s, with director of television research Dr. Herbert Ives at the helm. A prototype was tested in 1927, with Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover transmitting audio and video from Washington, DC, to AT&T's New York office.

Hoover on the line

President of AT&T Walter Gifford was at the Bell Labs office in New York to receive Hoover's call. Although both sides could communicate verbally, the video was only a one-way, 18 frames-per-second transmission.

Colorful communication

By 1929, those one-way videophone transmissions were upgraded to full color (unlike this photograph).

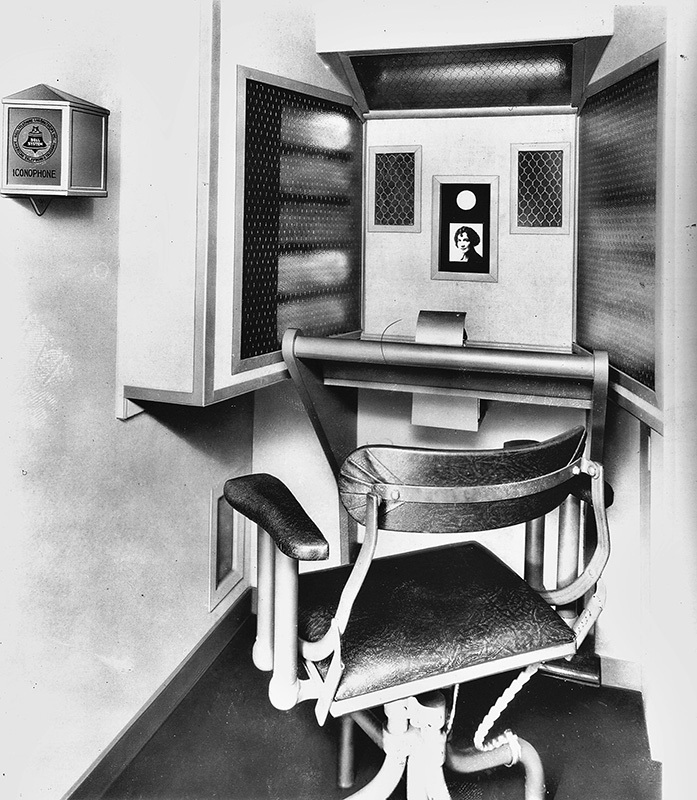

Iconophone

By 1930, Bell Labs had a working model of its two-way videophone, which it called the Iconophone (from Greek, meaning image-sound).

Movie magic

In 1927, videophone communication reached the popular consciousness through Fritz Lang's science fiction film Metropolis.

The first publicly operated, two-way picture-phone service in the world began in 1936 and was operated by the German Reichspost (post office). People in Berlin could get in some face time with others in cities like Leipzig until the service was shuttered due to World War II.

World's Fair debut

After decades of development, AT&T had a new Picturephone test system ready in 1956. But it was still a rudimentary device that could only transmit an image once every two seconds. By 1964, however, an improved experimental version had been completed and was ready to be unveiled.

The AT&T Picturephone (Mod 1) was displayed at that year's World's Fair in Queens, New York. It even hosted the first transcontinental video call from the Bell Systems Pavilion to Disneyland in Anaheim, California.

Unfortunately, the public's response to this modern-day marvel in communication was lukewarm. Many found the image quality subpar and the controls confusing. They were also put off by its high price tag.

Confravision

While AT&T had been pushing forward with its personal Picturephone systems, the British Post Office (later British Telecom) had been working on its own enterprise solution. Its Confravision studios were set up at branches as early as 1967 to offer a new mode of communication for high-level executives in business and government. Two or three studios could "teleconference" at one time. Confravision was initially limited to two interconnected locations in London, but was soon expanded to other UK and European cities.

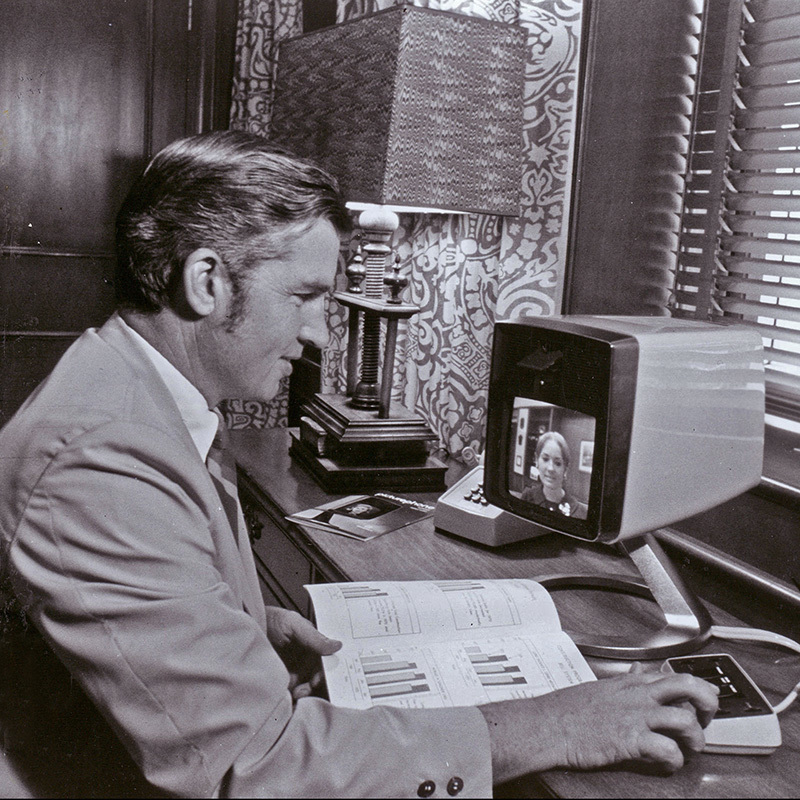

The Picturephone launches

Even after less-than-enthusiastic reviews, AT&T continued its trials of the Picturephone, installing booths in New York, Chicago and Washington, DC. Video calls cost around $16 to $27 for a three-minute session. That may seem like chump change until you figure that, adjusted for inflation, it'd cost about $120 to $200 now.

The commercial service was officially launched in 1970, but cost remained a factor. Monthly service fees started at $160 including only 30 minutes of video/talk time. People who used the system actually enjoyed one of its non-video perks: Using a system called APRIS, people could view documents from the company database onscreen.

Swedish envy

Ericsson, the Sweden-based electronics and communications maker, was so inspired by the technology being developed at AT&T that it began to invest in its own line of videophone products in the mid-1960s.

Like AT&T's test group, though, users preferred to use the device for sharing documents rather than actual person-to-person video calls. Separate video and audio lines were also required for the system, which added to its already hefty price tag.

Ericsson scrapped the project in 1977, but it seems it hadn't lost the taste for research in the video communications field. In 2012, it bought Telcordia Technologies Inc. (formerly know as Bell Communications Research).

The videophone future no one wanted

Despite having more than 60 years of research under its belt, AT&T still couldn't successfully market its videophone technology. Bell Communications Research (now divested from AT&T) was developing large-group video communications projects like its Video Window, and even though AT&T had similar office applications, it kept pushing the consumer angle.

In 1992, AT&T launched its VideoPhone 2500. This hybrid device worked over standard phone lines and could make normal audio calls, but also offered full-color video communication with other users. The device was launched with a $1,600 price tag. But by 1993, AT&T was offering $500 discounts. The consumer market, it seems, still wasn't ready to adopt this aging appliance of the "future."

Comments

Post a Comment